The Illusion of Control: Why GPS Systems Cause More Stress Than Traffic Jams

driver psychology, GPS stress, cognitive workload, human-machine interface, navigation systems, driving safety, cognitive science, driver behavior, automotive psychology, traffic psychology

Your GPS Is Your Biggest Enemy

When asked to name the most stressful part of driving, most people would point to heavy traffic or reckless drivers. However, research uncovered a more insidious culprit: the car’s own navigation system1.

The study found that interactions with the GPS were one of the most frequently identified causes of negative emotions like anger and disgust. Specifically, “navigation alerts” and “checking navigation” were more often cited as triggers for anger than high traffic density on both urban and major roads.

This finding flips the conventional script on driver stress. It shifts the focus from external factors we can’t control (like other cars) to the internal, system-level interactions within our own vehicle. It suggests that a poorly designed Human-Machine Interface (HMI) hijacks finite attentional resources, turning a tool meant to help into a primary source of cognitive friction and emotional stress.

The Engineering Reality: Modern navigation systems compete for the same cognitive resources your brain needs for safe driving. Every “recalculating route” announcement or confusing turn instruction creates an attentional bottleneck at precisely the moment when you need maximum focus.

This discovery that in-car technology can be a primary stressor opens a deeper question: what else is happening in our brains when we drive, especially when we don’t feel stressed?

Why “Easy” Drives Are Mentally Dangerous

It seems logical that driving in rush hour is more mentally taxing than cruising on a quiet, open road. While true for overall workload, research uncovered a dangerous paradox: unexpected events are far more mentally demanding during “easy” drives2.

Using electroencephalography (EEG) to measure brain activity, researchers found that surprise events—like a pedestrian stepping into the road or another car pulling out—caused a far greater cognitive jolt during normal, low-traffic hours compared to rush hour.

Why This Happens: During seemingly easy driving conditions, our brains enter a lower state of readiness. We are less prepared for a sudden threat. When an unexpected event occurs, the cognitive shock is more severe and taxing than in a high-traffic situation where our brain is already on high alert.

The study concludes that external events could lead to risky situations “especially with low traffic (normal hours),” turning a calm drive into a high-risk scenario in a split second.

“Easy” drives create a false sense of security—your brain downshifts into low-alert mode, making you more vulnerable to sudden surprises than during rush hour.

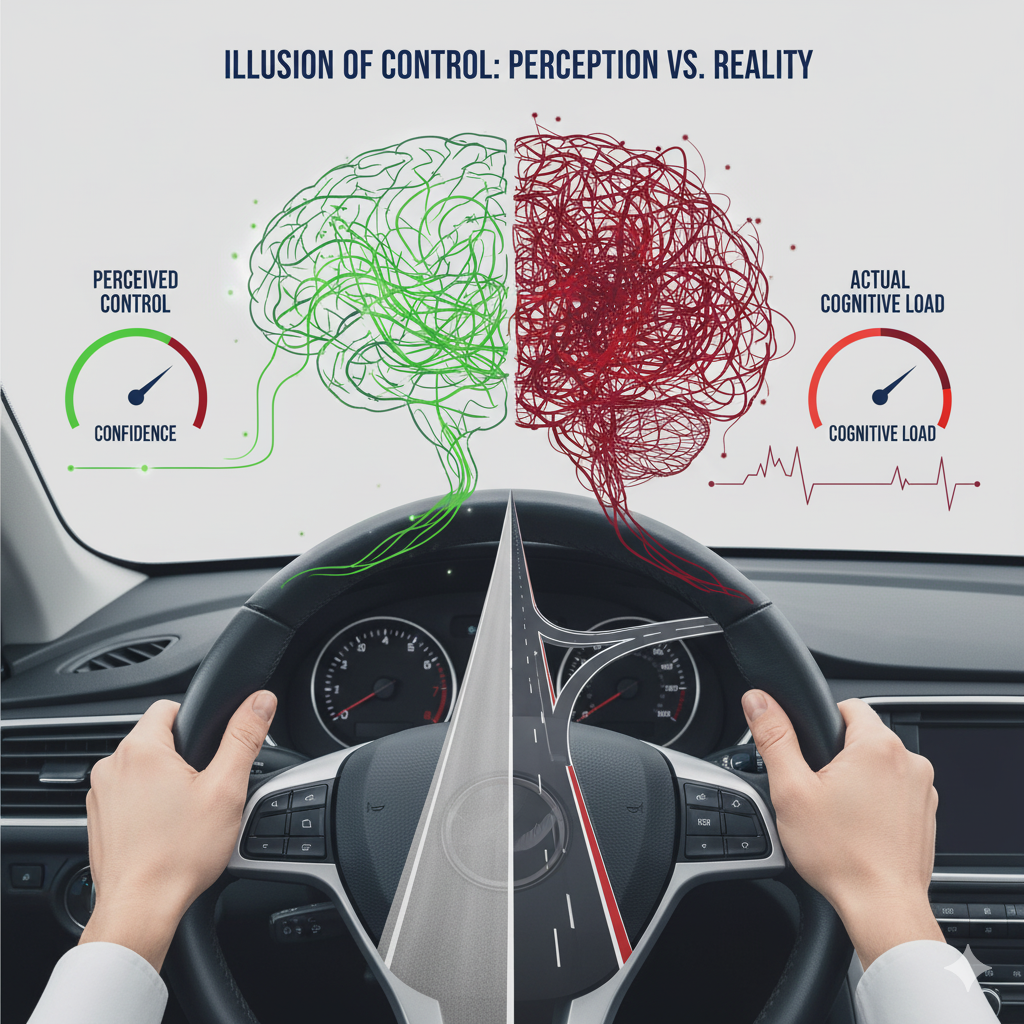

This paradox of ‘easy’ drives being mentally dangerous reveals just how unreliable our feelings are behind the wheel—a gap between perception and reality that researchers have now measured.

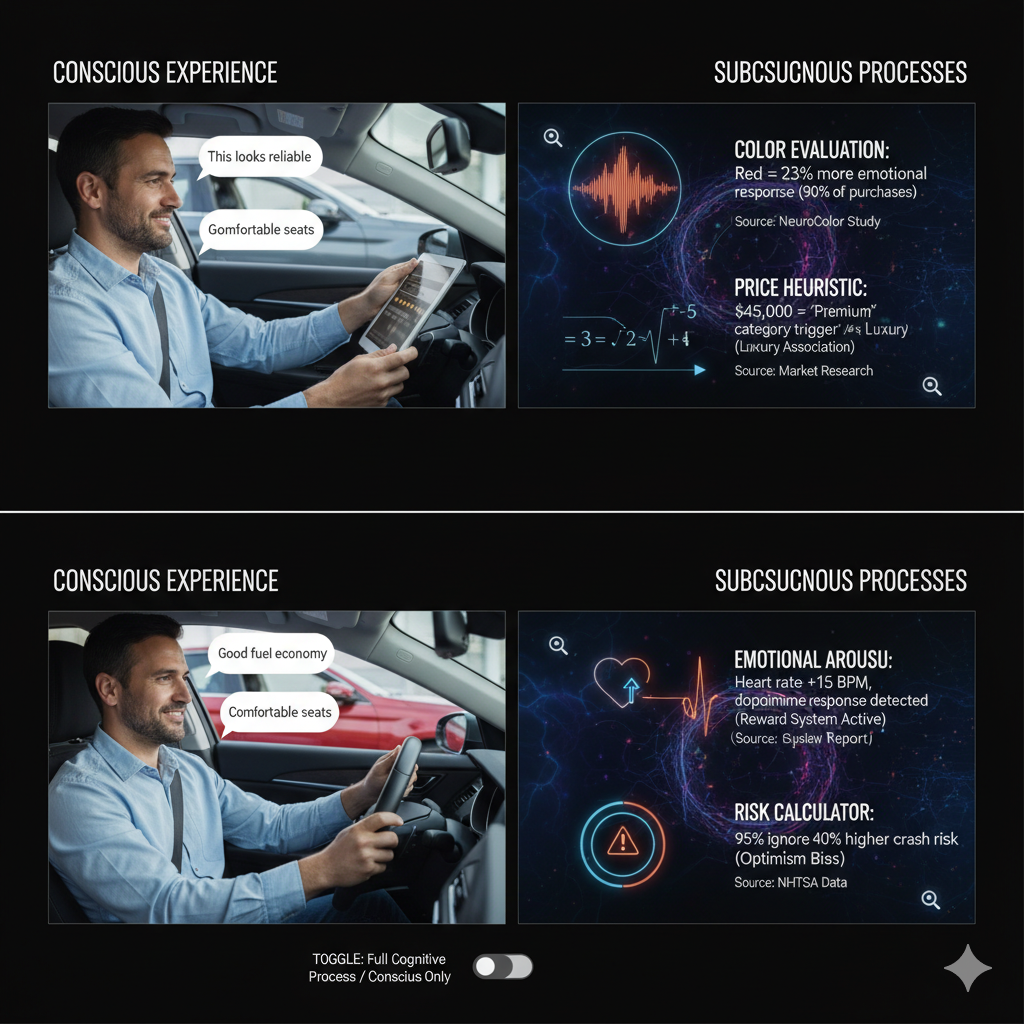

Your Brain Works Harder Than You Think

We tend to think we’re good judges of our own mental state. If we feel relaxed, we assume our brain isn’t working too hard. But research using EEG brain monitoring revealed a stunning disconnect between our perceived mental effort and our brain’s actual cognitive workload3.

When drivers were asked to rate their own workload using a standard questionnaire (the NASA-TLX), their subjective assessments showed no significant difference between driving in “Normal” and “Rush” hour traffic. However, the objective EEG-based measures told a completely different story, showing a significant increase in cognitive workload during rush hour.

The implication is profound: Our subjective feelings are an unreliable gauge of our mental state while driving. Our brains can be under significant strain even when we feel relatively calm, exposing the hidden cognitive toll of driving that our brains pay even when we feel at ease.

This disconnect between our feelings and our brain’s reality isn’t just an internal curiosity; it has profound implications for how we interact with the external world, including designs that have been flawed for decades.

Confusing Airport Signs: 40 Years of Bad Design

Have you ever glanced at an airport sign and felt a moment of confusion because the airplane symbol and the directional arrow seem to be in conflict? Research confirms that this confusion isn’t just in your head—it’s a measurable safety hazard caused by poor design4.

The experiment analyzed “stack-type” traffic signs, which combine an airplane pictogram with an arrow. Researchers found that when the pictorial information is incongruent with the arrow (for instance, the airplane points left while the arrow points right), drivers’ reaction times slow down and their accuracy in choosing the correct direction decreases5.

But here is the most surprising and frustrating part: this isn’t a recent discovery. Researchers flagged this exact issue in 1985. For nearly four decades, this known, performance-impairing design flaw has been permitted on roads worldwide, creating needless daily confusion for millions of drivers.

The Design Principle: Incongruent visual information should be avoided, as this might impair drivers’ performance. When symbols and arrows conflict, your brain must resolve the contradiction—stealing precious milliseconds from reaction time.

If such a basic design flaw can persist for decades, it raises a crucial question about modern vehicle design: are we making the same mistakes with new technology, particularly for our fastest-growing demographic of drivers?

Car Tech Ignores Its Biggest Users

In-vehicle technologies, from advanced safety features to infotainment systems, are often marketed as aids that make driving easier and safer for everyone. However, a comprehensive review of automotive design guidelines reveals that these systems are systematically failing to account for their fastest-growing user base: older drivers6.

The review found that most official automotive Human-Machine Interface (HMI) design guidelines do not adequately address the common age-related declines in: - Sensory abilities (vision, hearing) - Cognitive abilities (processing speed, attention) - Physical abilities (flexibility, strength)

Where older drivers are mentioned, the advice is typically too broad and lacks the prescriptive, actionable guidance that designers need.

The Critical Disconnect: The very demographic most likely to purchase and benefit from new technology is the one whose needs are least considered in the official guidelines that shape it. As our population ages and vehicle technology becomes more complex, this gap will only widen.

Rethinking the Driver’s Seat

These findings, taken together, paint a clear picture: the simple act of driving is far more psychologically and cognitively complex than it appears on the surface.

The Hidden Reality: - Your GPS creates more stress than the traffic it’s meant to help you navigate - Your brain’s guard drops during calm drives, making you more vulnerable to surprises - Your feelings deceive you about how hard your brain is actually working - Design flaws from 1985 still impair your performance every day - Modern car tech systematically ignores the needs of its fastest-growing user base

The familiar space behind the wheel is a dynamic intersection of human factors, neuroscience, and engineering—far more complex than the simple mechanical act of steering and accelerating.

The Driver’s Mind - Part 1 of 5

Explore the hidden psychology of driving—from cognitive illusions to the future of human-vehicle interaction

Series Posts:

- Part 1: The Illusion of Control - Why GPS systems cause more stress than traffic jams

- Part 2: The $10,000 Paint Job - The psychology behind automotive color choices

- Part 3: Your Brain on Autopilot - How automation changes driver psychology

- Part 4: The Invisible Passenger - Hidden psychological factors in driving

- Part 5: The Mind-Reading Car - Future of cognitive automotive interfaces

References

Footnotes

Weber, M., Giacomin, J., Malizia, A., Skrypchuk, L., Gkatzidou, V., and Mouzakitis, A., 2019, “Investigation of the Dependency of the Drivers’ Emotional Experience on Different Road Types and Driving Conditions,” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 65, pp. 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2019.06.001.↩︎

Di Flumeri, G., Borghini, G., Aricò, P., Sciaraffa, N., Lanzi, P., Pozzi, S., Vignali, V., Lantieri, C., Bichicchi, A., Simone, A., and Babiloni, F., 2018, “EEG-Based Mental Workload Neurometric to Evaluate the Impact of Different Traffic and Road Conditions in Real Driving Settings,” Front. Hum. Neurosci., 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00509.↩︎

Di Flumeri, G., Borghini, G., Aricò, P., Sciaraffa, N., Lanzi, P., Pozzi, S., Vignali, V., Lantieri, C., Bichicchi, A., Simone, A., and Babiloni, F., 2018, “EEG-Based Mental Workload Neurometric to Evaluate the Impact of Different Traffic and Road Conditions in Real Driving Settings,” Front. Hum. Neurosci., 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00509.↩︎

Di Stasi, L. L., Megías, A., Cándido, A., Maldonado, A., and Catena, A., 2012, “Congruent Visual Information Improves Traffic Signage,” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 15(4), pp. 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2012.03.006.↩︎

Di Stasi, L. L., Megías, A., Cándido, A., Maldonado, A., and Catena, A., 2012, “Congruent Visual Information Improves Traffic Signage,” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 15(4), pp. 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2012.03.006.↩︎

Young, K. L., Koppel, S., and Charlton, J. L., 2017, “Toward Best Practice in Human Machine Interface Design for Older Drivers: A Review of Current Design Guidelines,” Accident Analysis & Prevention, 106, pp. 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2016.06.010.↩︎