Birth of Motion: Early Automotive Innovation (1832-1945)

automotive history, car invention, Otto engine, Ford assembly line, automotive innovation, vehicle evolution, industrial revolution, mass production

The Evolution of the Automobile - Part 1 of 3

Explore the birth of the automobile—from the first engines to revolutionary production methods

Series Posts:

- Part 1: Birth of Motion (1832-1945) - Early innovations & pre-WWII era

- Part 2: The Golden Age (1945-1990s) - Post-war boom & cultural icons

- Part 3: Electric Dreams (1996-Present) - The green revolution

The story of the automobile is one of humanity’s greatest technological triumphs. From the first sputtering engines to elegant luxury machines, the period between 1832 and 1945 laid every foundation for modern transportation.

This was an era of bold inventors, daring innovations, and societal transformations. Let’s explore the key milestones that turned the dream of horseless carriages into reality.

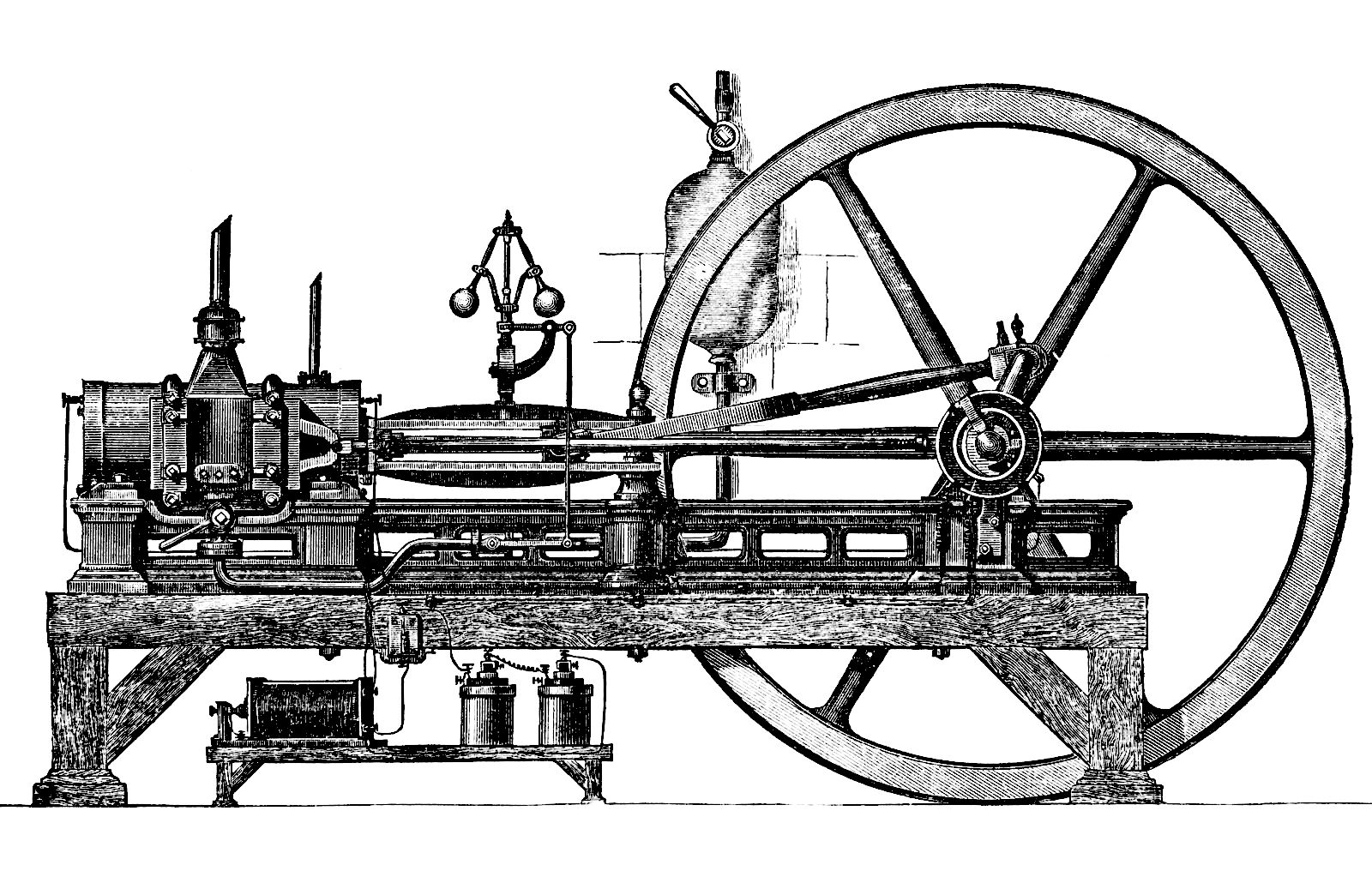

The First Spark: Otto’s Revolutionary Engine (1876)

Before cars could exist, they needed a heart—a reliable power source that could convert fuel into motion. Nikolaus August Otto, a German inventor, provided that breakthrough in 1876 with his four-stroke internal combustion engine.

Otto’s engine worked on a simple but brilliant cycle: intake, compression, power, and exhaust. This four-step process burned fuel more efficiently than earlier two-stroke engines, saving gas and reducing emissions. Though it produced just 2-3 horsepower, this design became the blueprint for virtually every gasoline engine that followed.

Without Otto’s innovation, the automotive revolution would have remained a fantasy.

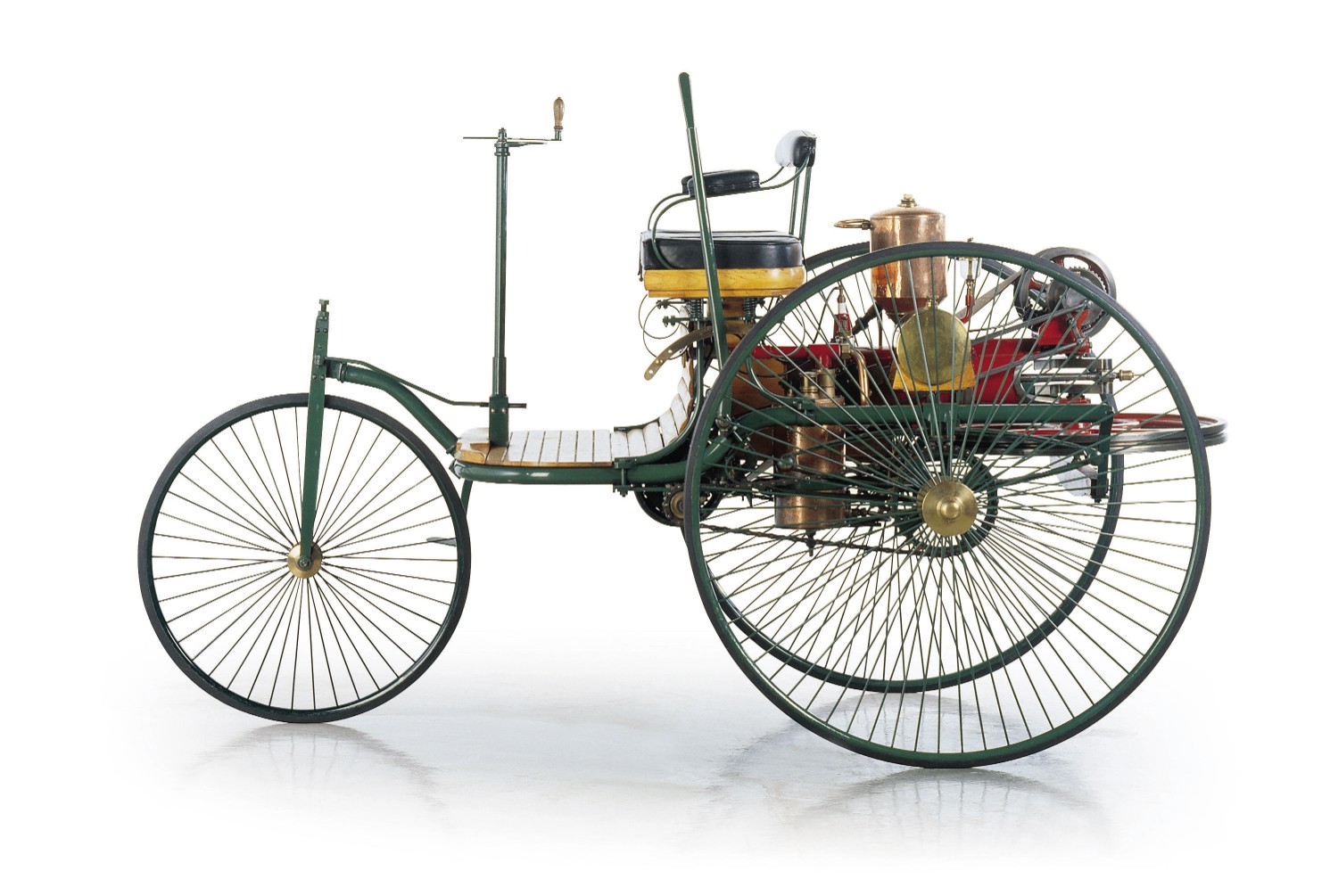

The First Automobile: Benz Patent-Motorwagen (1886)

Ten years after Otto’s engine breakthrough, Karl Benz combined engineering genius with entrepreneurial vision to create the Benz Patent-Motorwagen—the world’s first true gasoline-powered automobile.

This three-wheeled vehicle featured a single-cylinder four-stroke engine mounted at the rear, powering the back wheels. It could reach a top speed of 16 km/h (10 mph)—not fast by today’s standards, but revolutionary for 1886. The Motorwagen used a tiller for steering, wire-spoked wheels, and a lightweight steel frame.

The vehicle’s reliability was famously proven by Benz’s wife, Bertha Benz, who took it on a daring 100-kilometer journey in 1888 without her husband’s knowledge. This publicity stunt demonstrated that automobiles were practical for real-world travel, not just laboratory curiosities.

Karl Benz’s invention launched what would become Mercedes-Benz and fundamentally changed personal transportation forever.

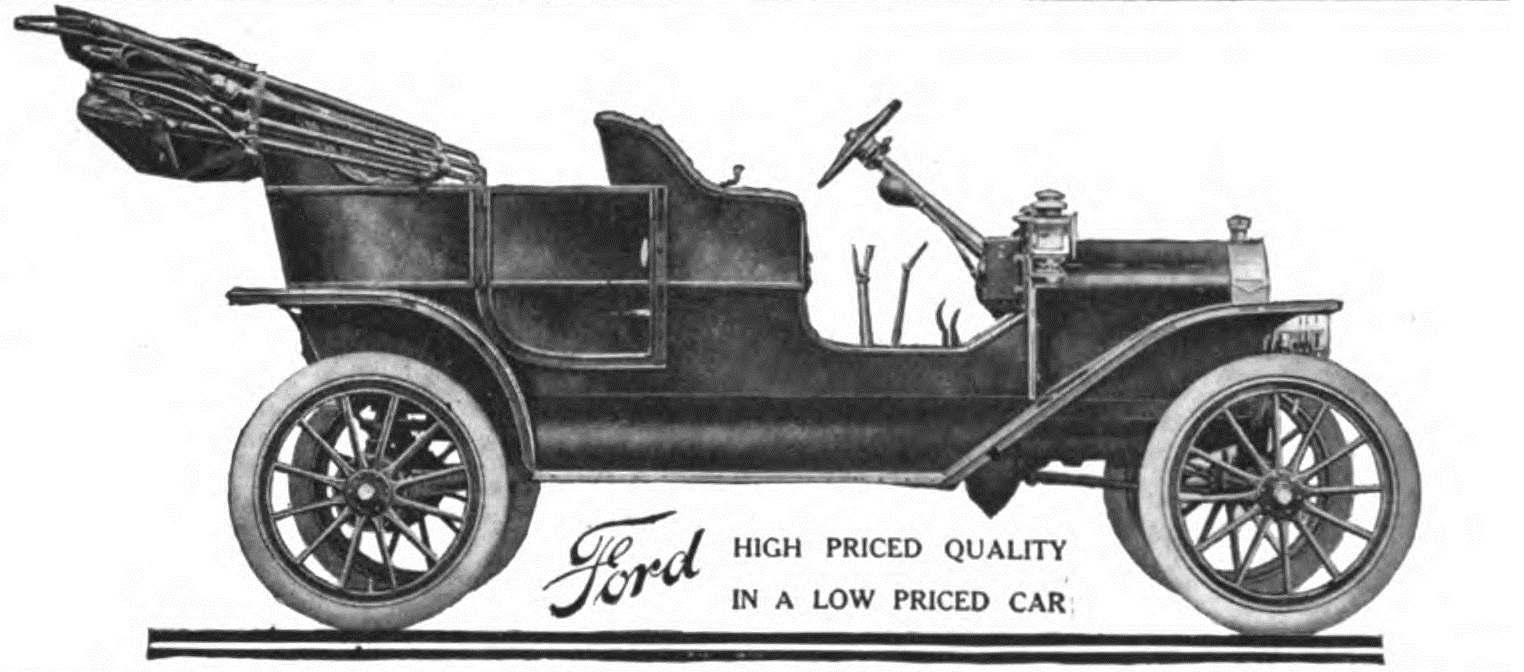

Mass Production Arrives: Ford Model T (1908)

While Benz invented the automobile, Henry Ford made it accessible to the masses. The Ford Model T, introduced in 1908, transformed cars from luxury items for the wealthy into practical tools for ordinary Americans.

Ford’s genius wasn’t just the car itself—though its 20-horsepower four-cylinder engine, planetary transmission, and strong vanadium steel frame were impressive. His real revolution was the moving assembly line, perfected in 1913.

By breaking down car production into simple, repetitive tasks, Ford slashed manufacturing time from 12 hours to just 90 minutes per vehicle. This efficiency allowed him to continuously lower prices. A Model T cost $850 in 1908 but just $260 by 1925—affordable for middle-class families.

Over 15 million Model Ts were sold before production ended in 1927. Ford didn’t just build cars; he democratized mobility and transformed American society. Workers could now live farther from factories, rural families gained access to cities, and the automobile became a symbol of freedom.

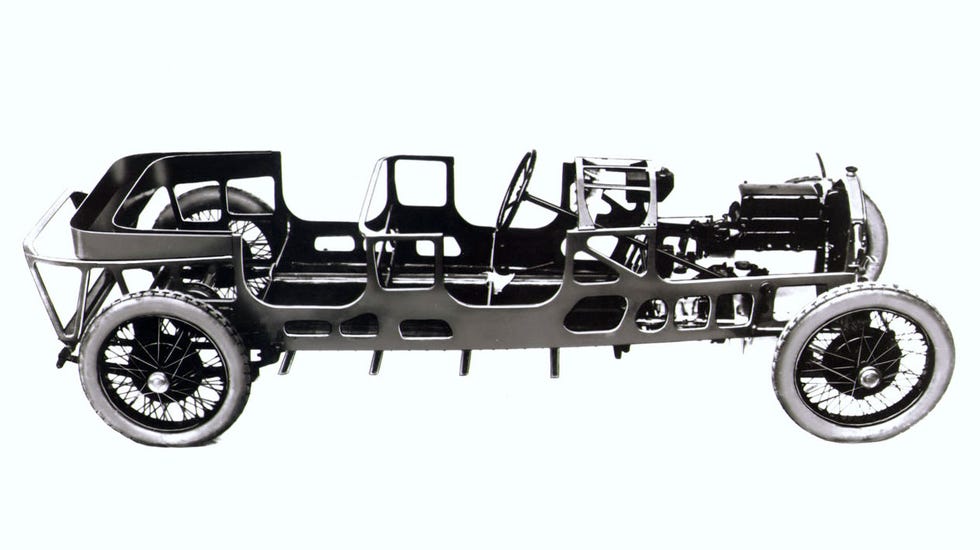

Engineering Evolution: Lancia Lambda (1922)

While Ford focused on affordability, Italian automaker Lancia pushed the boundaries of automotive engineering. The Lancia Lambda, introduced in 1922, pioneered monocoque (unibody) construction—a design principle that dominates modern car manufacturing.

Traditional cars used a separate ladder frame chassis with the body bolted on top. The Lambda integrated the body and frame into a single self-supporting structure. This approach offered multiple advantages:

- Lighter weight without sacrificing strength

- Lower center of gravity for better handling

- Improved rigidity throughout the vehicle

The Lambda also featured a narrow V4 engine with a single overhead camshaft—advanced for its time. Its independent front suspension with hydraulic shock absorbers and coil springs was a first for production cars, delivering superior ride comfort.

Built from 1922 to 1931, approximately 13,000 Lambdas were produced across nine series. Engine displacement grew from 2.1L (49 hp) to 2.6L (69 hp), with top speeds of 70-75 mph—impressive performance for the era.

Today’s cars still use Lancia’s monocoque principles, making the Lambda one of history’s most influential automotive designs.

Aerodynamics Takes Flight: Chrysler Airflow (1934)

As cars became faster, wind resistance became a critical concern. The Chrysler Airflow, produced from 1934 to 1937, was America’s first serious attempt at streamlining to reduce drag and improve efficiency.

Chrysler engineers, with input from aviation pioneer Orville Wright, conducted extensive wind tunnel testing to optimize the Airflow’s shape. The result was a smooth, rounded body that sliced through air with minimal resistance. The car also featured unibody construction for added strength and reduced weight.

Unfortunately, the Airflow was a commercial failure. Its unconventional appearance clashed with consumer preferences for traditional automotive styling. Many buyers simply weren’t ready for such radical design changes.

Despite poor sales, the Airflow represented a crucial milestone in automotive aerodynamics. Its principles influenced car design for decades, proving that even failures can drive progress.

Pre-War Luxury: Engineering Meets Art

Before World War II disrupted civilian production, luxury automobiles reached extraordinary heights of craftsmanship and engineering. These weren’t mere transportation—they were rolling works of art that showcased cutting-edge technology and exquisite hand-built details.

Elite manufacturers like Rolls-Royce, Packard, Duesenberg, Mercedes-Benz, and Cadillac catered to the ultra-wealthy with bespoke vehicles featuring:

- Hand-crafted bodywork by renowned coachbuilders

- Powerful multi-cylinder engines (V12 and V16 configurations)

- Advanced suspension systems for supreme comfort

- Lavish interiors with premium materials

The French Art of Luxury

France led the luxury segment with legendary marques like Delage, Delahaye, and Bugatti—names that combined elegant styling with sophisticated engineering. These manufacturers crafted cars that were as beautiful as they were technically impressive.

American Excellence

In the United States, Packard, Pierce-Arrow, and Peerless (the “Three Ps”) represented prestige and innovation. Packard introduced the modern steering wheel and pioneered V12 engines for smooth, powerful performance.

These pre-war luxury vehicles were more than transportation—they were symbols of wealth, status, and technological progress. They also served as testing grounds for innovations that would eventually trickle down to mainstream automobiles.

The Dawn of Modern Motoring

The period from 1832 to 1945 witnessed the automobile’s transformation from experimental oddity to essential technology. Visionary inventors like Otto, Benz, Ford, and Lancia established engineering principles still in use today.

From Otto’s four-stroke engine to monocoque construction, from mass production to aerodynamics—each innovation built upon the last, creating the modern automobile industry. The pre-war luxury marques demonstrated what was possible when engineering met artistry without constraint.

World War II temporarily halted civilian car production, but the stage was set for the automotive boom that would follow. The foundations had been laid; now came the golden age.

*In Part 2, we’ll explore how post-war innovation and cultural shifts created automotive icons that defined generations.